Glen Seator: Making Things Moving Places

v14 / Text and Catalogue

Lay-flat softcover binding with a stitched book block and reinforced spine

Page dimensions: 19 x 26 cm (7.5 x 10.25 in.)

48 pages

Catalogue of 127 sculptural works

Text by Nina Holland: „Looking and Listening: A Collaboration with Glen Seator“

The entire essay can be read below.

Looking and Listening: A Collaboration with Glen Seator

First Encounters

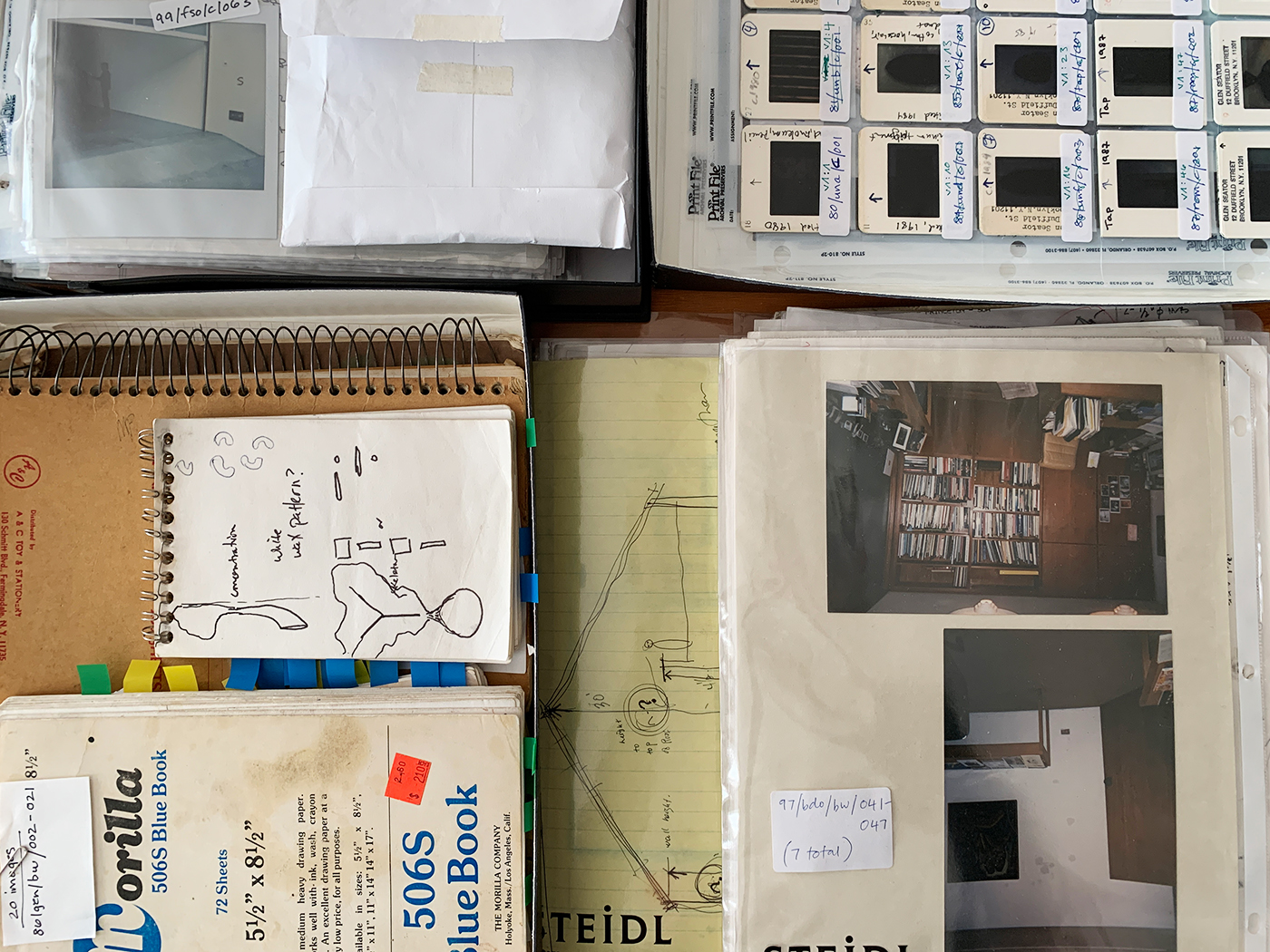

I remember the first day I began to work with Glen Seator. It was a Wednesday, January 24, 2001. He arrived in Los Angeles with fifteen well-battered boxes filled with photographic materials of all sorts, writings, drawings, blueprints, engineering studies, crumpled bits of paper scribbled with things to remember, receipts, notebooks, sketches, video footage, correspondence, court filings, budgets, production schedules, small chips of building materials, layers of dust, and several years worth of bills and termination notices. He was weary from his encumbered journey.

I had anticipated his arrival for some time. Several months earlier, he had telephoned from New York to introduce himself. We were both working on projects for a Viennese museum with a satellite in Los Angeles. Seator had just completed the long planning phase of a collaborative work he hoped to realize in the coming year. I was in the middle of a translation and several editing projects when I received his call. „I’d like to talk to you about some things I’m working on, if you have a few minutes,“ he began. He related that he would be in Los Angeles „by at least November“ for an artist residency at the Getty Research Institute. He was moving in a new direction with his work and intended to get a photography project underway during his stay. „But,“ he said, slowing down, „I also think it’s important to record the work I’ve made to date in a book. A lot of my work hasn’t been seen. It hasn’t circulated. A lot hasn’t been published. People have seen one or two, maybe a few works, but there’s no publication that brings everything together. It’s been a problem,“ he admitted.

But the problem ran deeper than not having a comprehensive monograph: a book, he insisted, could not capture the experience of the work. The work can’t be reduced to language or a photograph. In a sense, the work is about what language and photography are not.“ This was an interesting problem, I thought. What he wanted from a book was not attainable. He was certain of this. Even so, he seemed to have no intention of giving up. „What if someone struggled to capture the work and failed? The failure, if it were done the right way, could be very revealing,“ I suggested. Seator was silent. „I mean, there are many different ways of writing about art. You-re not limited to historical and critical approaches. It would be fascinating to see how close writing could come to capturing your work, and, along the way, something might be learned by looking at how the writing fails…assuming that it does fail.“ Still he said nothing for a moment, then asked, „Can we talk about this more when I get to LA?“ Of course, I agreed.

Following this first conversation, he called occasionally – nothing new, he was just checking in. November passed, then December. He remained in New York; although, he assured me, he was trying his best to leave. The difficulties that prevented him from traveling were unclear. Halfway through January, I was really curious to know what had happened to him. What of his plans? His residency?

Then, with little warning, one Wednesday, he did arrive. He telephoned, „I’m walking into the compound,“ he announced, in good spirits. „The compound?“ „The scholar apartments at the Getty. I don’t know about this. I’m not much of a group person,“ he went on. „In Los Angeles? You’re here?“ „I’m here. I’m at the corner of Sunset and…oh, what’s the other street?…Westgate.“

It turned out that he had moved in just down the block from me. It was quite a surprise. „Well, I’m moving!“ he laughed at the coincidence, and then, without hesitation, added, „By the way, I have some things that you might find interesting. Do you have space for a few boxes? You can keep them as long as you want. I’ll bring them right over.“

A few minutes later, I met Seator for the first time as he wrestled fifteen boxes – his archive – over the threshold of my home. „You’ve got to be kidding! Where are we going to put all of this? How long is it going to be here? How much of this is really necessary?“ my husband protested. I had no answers. I had only agreed to continue a conversation. Where I fit into this picture, and why, was an unknown. If Seator knew, he had not filled me in.

He had been consistently upbeat on the phone, but in person he seemed nervous and distracted. The difference was jarring. He suggested a walk. He wanted to get a sense of the neighborhood and resume our discussion, so we headed down Westgate toward a favorite local bookstore. Soon his attention was drawn to something I had never noticed: the mailboxes standing at curbside were each encased in a monolith of concrete, or brick, or stucco. He inspected each one, gradually regaining his composure and humor. „I’m interested in what you’ve said about writing. Is this something you’ve been working on?“ he asked.

„Yes…for about five or six years,“ I told him. „I started experimenting with writing when I worked with David Wilson at the Museum of Jurassic Technology. We wrote all the time, for different purposes, but it was always important not to interpret or explain the museum in the process. It was incredibly difficult at first, but I found, over time, that this non-interpretive way of working opened a different range of possibilities than critical approaches…and, for me, the results seemed more interesting, certainly more appropriate in that context. It was close to translation – a way of animating, or sometimes extending, the project, rather than pinning it down to a particular interpretive position.“ Seator listened carefully.

„You’ll find this funny,“ he responded, „I think I forgot to tell you when we first spoke, but that’s one of the reasons I called you. I found out that you had worked at the Museum of Jurrasic Technology. I love that place!“ His sudden enthusiasm was startling. „Of all the projects I’ve seen over the past few years‚…“ he searched, „it’s been deeply moving to me. I’ve gone by every time I’ve been in LA. I’ve sent other people there too.“ I was so pleased to hear this, but could not put together what little I knew of Seator’s work with his interest in the museum. It was yet another point of confusion.

We were now seated in a dim corner of the bookstore, and I asked him to describe the new direction of his work. He unfolded a napkin, took out his pen, and began to sketch several elevations of buildings, recognizable types of vernacular architecture, which would be the subject of a new series of photographic works. He recounted the course he had taken from building to photography via the architectural drawing. He described his anticipated work methods and the technical feats he would have to accomplish in order to produce a series of impossible views of buildings – views unavailable to the human eye through any other means. All of this was a logical extension of his sculptural work, he pointed out, but it was something else as well, something more practical but no less important. His sculptural work was completely unviable within the traditional channels of the art world. He had never earned an income from his work. A rental unit in his Brooklyn home had supported his basic expenses throughout his career. In many cases, he had pulled together his own limited resources, accumulated debt, and relied on hundreds of volunteers to accomplish his projects. He never compromised, he never failed to fully realize a project, but the personal cost of this had been excruciating, he confided. He did not foresee giving up built projects altogether, but he hoped his photographic work might stabilize his situation a bit.

„I really need help with this,“ he muttered absentmindedly as he looked into the next room of the bookstore. I thought, perhaps, he did not intend me to hear what he said. But then he repeated his thought, „Yes. I really need some help. Would you be willing to help me write about this? I’ll need something in writing if I’m going to get this project off the ground.“ It sounded easy enough, I told him. „Why not? If you send me what you have, I’ll see what I can do.“

I returned home to the fifteen boxes Seator had left a few hours earlier. Was he kidding? Where were we going to put all of this? How long was it going to be here? How much of this was really necessary? They were good questions. Still, I had no answers.

The Clues

I set out to write something simple, short, straightforward: a project description could be completed in an evening. I thought it would suffice to transcribe what Seator had told me about his plans. A few days later, I had produced a draft, and I met with him to look over it.

He circled different phrases in the text, and then, without explanation, spoke broadly of his work, life experiences, people he had known, questions he had considered. He leaped from one subject to another…There were mistakes in some architectural drawings commissioned by an institution, and when he went to form footings, it was a disaster. Mistakes just weren’t allowed in his family. There were no erasers. His grandfather, who was the son of an architect, never allowed erasers. The fact that there were architects in his past was a secret…thank goodness for Nonny. He never would have survived without his grandmother…He had considered a life in theater when he was in college – readers‘ theater, that is, because he didn’t want to take the leap into acting and deal with the full body… This went on for about two hours. The episode was erratic and baffling, and, at the same time, completely engaging. I had questions, but his answers were too far afield for any immediate, practical use. I pulled together what I could in the way of notes and walked home, thinking as I went that the project now seemed larger and more vague.

Seator continued to tell more of his story in the following days. It flowed from one conversation into another, one day into the next. His calls became frequent and longer in duration. He joined my family often for lunch and dinner. Within a few weeks, our conversations were taking up at least eight hours of every day, and sometimes many more. I was fascinated by the whole sprawling process. It seemed like chaos at first, but portions of Seator’s disjointed story were beginning to hold together for me. His responses to questions were beginning to make sense as answers.

At some point, I finished the project description, although our discussions had already progressed well beyond it. Seator was optimistic about pursuing the collaboration further. We agreed that our ongoing conversations were a viable basis for a book, and we began to discuss the form it might take.

There was nothing unique about the way our project expanded. I saw examples of ballooning projects everywhere in Seator’s record. If a single image was requested for a magazine article, he insisted on three or four, and if the magazine agreed, he would then try for nine or ten: „The work doesn’t function from one view. If it’s only shown from the front, it looks like something it’s not. A single image can do a lot of damage,“ he explained. Catalogues of individual projects had to include other works as well, ideally projects from the early 1990s that marked his transition into architectural subjects and methods. None of his most celebrated works would have been possible if he had not pushed limits. In the most extreme case, Seator was given $13,000 to complete a project. By the time he was done – having scraped together something closer to $37,000 and a small army of volunteers – the cost of producing the project under normal working conditions was estimated at $600,000.

I wondered how a book could be structured around the internal necessities of the work. It seemed counter-productive for Seator to push for what was needed. If the work would be difficult to capture using all available resources, arbitrary limits would only cut off some of the most interesting questions. But what was necessary?

I set aside time each day to look through the archive. Disorganized and perplexing, it was a great puzzle, and the vast majority of pieces were unfamiliar: images of stud finders attached to walls, glass and liquid surfaces reflecting surrounding places, spills of plaster, loosened screws projecting from small cuttings in walls, pieces of plasterboard, incisions in floors, bins of sweeping compound, electric bulbs, light fixtures, expanses of raw framing, large rolls of tape, Polaroids of storefronts, snapshots of building interiors, and so forth. The materials Seator had amassed seemed endless and indecipherable. All the familiar images of his well-known works were there, but in relation to this record of his activities over a fifteen-year period, they seemed to recede into insignificance. They were indeed misleading, as he had indicated.

I was on my own putting the puzzle together. Seator offered only one clue: „It’s important to understand how the work was made.“ This could be ascertained through careful observation, he insisted.

At first, I struggled to find the work. It was not easy to distinguish what was work from what was not. Was the stud finder attached to the wall a work in itself, or was Seator marking an underlying screw in the process of making another work, perhaps a Wallraising? What about a dozen stud-finders over a span of wall? If they were indications of process, could this process be considered part of the work, and which work did it lead to? There were spills of plaster. Some gushed through simple rectangular holes in walls, some through T-shaped, wood-framed openings. Some were at head level, some at waist level. Most had splattered freely down a wall’s surface, but at least one spill had been formed to a tidy step where floor met wall. How many spills? Where and when did each occur? The door buzzers, the electrical wires, the doorknobs – where did these fit into place? Views through windows were recorded. Which windows framed these views, and what rooms were they part of?

I was not alone in my confusion. Seator’s ongoing story was speckled with accounts of people who had missed the work. „Many of the projects were mistakes, in a sense, deliberate mistakes that caused the people who viewed them to make mistakes,“ Seator offered. From 1990 to 1995, he maintained a studio at 135 Plymouth Street on the Brooklyn waterfront, where he made a series of works in which his studio served as both subject and material. His visitors often mistook bulges in walls and puddles of water and wet paint for failed home improvement projects. Occasionally a visitor would blunder into a puddle, much to Seator’s delight. He cut into the existing walls of his studio, loosened the underlying screws, and pulled sections of the wall slightly forward. The forms of these Wallraisings coincided with various features of the room. The first was a sort of „failed door.“ For others, he incised the plan view of the studio into its own walls. „I found that by varying the scale of these Wallraisings, I could make them almost disappear,“ he told me. „The smallest version, which was about fifty inches in length and width, could be immediately comprehended in relation to the surrounding space. But the largest version, a little more then twice the size of the smallest one, was practically invisible. Very few people noticed it.“ Some of his most physically demanding works were the most difficult to see. Preventative Measures, realized at the National Gallery of Contemporary Art in Warsaw in 1994, was a case in point. Seator set out to perfect a late-nineteenth century gallery built in the Greek style according to its own aesthetic principles – using nothing but masking tape and thin strips of wood. After he had labored many days, stretching and smoothing bands of tape to completely cover every surface of the gallery up to the ceiling, including windows and doors, many viewers confronted what appeared to be an empty room and asked, „Where’s the work?“

The archive was no less elusive. It took more than nine months of uninterrupted study before I was certain I had found the work – just over one hundred projects – and put all the details in place. There were only a few scraps remaining that I had not been able to identify. My initial experience of the archive as endless and indecipherable was now exactly reversed: each element of the mass was now so distinguishable, I could not have possibly mistaken it for any other. By bringing together all of these materials, it was possible to understand how Seator made his work and situated it for presentation. It was also possible to identify various methods and objectives in the way he recorded it all.

The Process

First, Seator would select and observe a site. He looked, surveyed, measured, photographed, and drew. He studied every material used to make the site and located the manufacturers of the materials. He tracked down construction records, construction standards, and building codes. He researched the site’s history and its surroundings. He studied the unremarkable comings and goings of people, noting how they passed through the space, what they did, what they observed and failed to observe. His objective was to attain a comprehensive understanding of the physical, psychological, and cultural aspects of the particular place.

Next Seator would render his observations in a tangible form. For the most part, he limited himself in subject and material to the given – the observed site and the materials of its construction and/or maintenance. Some projects were inscribed directly on the observed place by cutting into existing walls and floors. Others involved an uncompromising process of reconstruction in which the smallest observed details „were rendered within a sixteenth of an inch of their lives.“ The materials he used for these reconstructions were a precise match: concrete, for example, was not just concrete, but a specific combination of aggregate and cement poured and formed according to exact specifications. Bricks were not just any bricks, but a certain type of a particular color manufactured by a single brick company in a specific location. Every nail and screw was driven in a manner specified by the artist. This level of precision and control extended to every aspect of a project. There were also psychological and social dimensions which became part of making a work – personal struggles, increasing debt, lawsuits, disputes with presenters. Several projects required mobilization of extensive communities of specialized craftsmen and construction experts. All of this, according to Seator, was relevant to understanding the nature and scope of his artistic endeavors.

Placement was a critical aspect of each work. The most basic situation involved a place and a representation of this place in close proximity. Seator began to work with this arrangement in 1990 with a series of studio projects that he conceived as „portraits of a place, made from and on the place itself.“ The process, he imagined, would be „similar to a person tattooing an image of himself on his own face.“ His Wallraisings functioned along these lines, as did his series of Planned Puddles. The latter began in the studio in 1992. Seator cut the plan view of his studio into the floor. He pried up the floorboards surrounding the incised shape, fixed them in position with nails, and sealed the incision with silicone, thus creating a shallow receptacle that would collect water as Seator mopped the studio floor. „It was a reduction, a condensation of the floor and its maintenance. It was a way of making the floor more understandable, manageable, as a thing…something that could be gotten in one look, one still shot. These were not maps that took the viewer somewhere else; rather, they were maps of here that showed what here was not.“ The works could not be transported beyond the boundaries of the studio; however, the procedures and methods used to make the works could be carried out elsewhere in accordance with the given conditions of the new site. In this way, the series of Planned Puddles and Wallraisings expanded to locations in New York City, Lodz, Purchase, and Los Angeles.

Preventative Measures also worked on a model of proximity, with one important deviation: the viewer was placed within a place and a representation of this place which were coterminous. The representation blocked access to the very walls and floor that it represented. The architectural reconstructions, which followed closely on the heels of this Warsaw project, further obstructed the relationship between place and its representation through distance, time, or terms of access. Though permanently tied to a particular place, the architectural reconstruction could be let out on a leash to travel to new locations „much the way a photograph is sent out into the world,“ Seator explained. The reconstruction could travel to the next room, down the street, across town, or into another state or country. At the same time, the place to which this reconstruction would remain tethered would undergo various changes over time, including possible destruction. On one occasion, Seator determined that the place and the reconstruction could only be shown side by side. Consequently, the work was destroyed after exhibition, leaving the generative site in the world alone. In other circumstances, the generative site was already destroyed or in the process of being destroyed when the work was made. In these cases, the reconstruction existed in relation to a mere documentary record, or memory, of its twin. „It was a simple method of working that gave access to an incredibly broad range of concerns,“ Seator reflected, „…problems of observation, childhood training, narcissism, anxiety, memory, control….“

Using a combination of photography, video, architectural drawing, and models, Seator worked in a consistent manner to document the full range of his activities, from observation and making to situation and presentation. He knew precisely what he had compiled in the archive and why. He also knew which views were missing, how they could be reconstructed, and where source materials could be found. In many cases, but not all, these missing views were minor details that would have benefited a viewer only marginally. The work of tracking down the documentation, on the other hand, was significant. Seator insisted that every last detail should be retrieved….There was an amateur photographer who managed a hotel in Fisherman’s Wharf. He spent several weekends photographing at Capp Street. He might have shots of the back of the work…Footage of Preventative Measures was deposited at a local television station. The videographer was shooting a lot of other things, so it’s interspersed with other footage on several different tapes. It’s there, but someone has to go to the station and get access to the tapes. The station say it doesn’t have any tapes, so someone will need to pull some strings…There are no images of the White Columns tank in situ. BG can help get the architectural drawings of the gallery. Then the work has to be repaired and reinstalled and photographed. There are three views that have to be filled in – a basic installation view, the connection of the electrical cord to the gallery wall, and a view from above, which should be dropped into a plan view of the gallery in Photoshop. Seator had made some of these works up to ten years earlier, but he was still trying to close as many gaps in the record as possible. He passed along the list to me so that I could help as well.

On the most basic level, Seator intended the documentary record to define the scope of his project and preserve, in a useful form, critical information about the work itself. At a deeper level, the documentation was a necessary part of his work. „Many of the works functioned as markers of change in the built landscape,“ Seator told me. „This is really key. We need to make a list, Hints for Historians, and put changes in the built landscape at the top.“ Almost every reconstruction captured, to the extent possible, a place at a particular moment in its physical and cultural history. At the same time, though, the reconstruction also brought to the fore the distance between itself and the generative site. The latter, fixed in a particular location, did not exist in a frozen or idealized state. The architectural reconstruction, fixed in a particular physical form, could travel under certain circumstances to new locations. The work did not cease to function as its relationship to the generative site changed. On the contrary, as Seator asserted many times in our conversations, this elasticity was at the very heart of his project. The relationship between a place and its representation was both permanent and changeable. Seator compiled a documentary record in order to make the evolving relationship between the two at least partially accessible to a viewer.

The question was, how? Seator had mentioned the problem in our first conversation, and he had suggested the answer as well: a book. Now, with a different perspective of the work and the artist, I realized how little I had understood of the problem then. Nothing, in fact. All of this – observing, making, placing, documenting – was the full picture. All of this was the work. I was filled with sympathy for Seator as I thought about the way he had persisted in collecting and maintaining this massive record, and how he had used every opportunity to bring an insignificant fraction more of it into public view. A book would not deliver anything approximating a direct experience of the work; however, it could make accessible this wide range of processes that were an inextricable part of it.

As I worked with the archive, Seator and I also collaborated on a number of documentary writings. This was, by far, the most problematic aspect of the documentary process for Seator. Language was not only antithetical to the impulses of his work, he explained, but it could also obstruct the sorts of experiences the work was made to provoke. „My work doesn’t illustrate anything. It can’t be reduced to an explanation, a theory, a concept. It operates through experience, not language. Every time you use language, there’s a risk, a real danger, that the words will substitute for the experience, that they’ll cut off experience and shape it in a way that’s exactly what the work it not about,“ Seator warned. His work functioned more along the lines of poetry than prose. It could not be expressed other than in the form he had rendered it. The interchangeability and malleability of language was ill-suited to the physical precision he cultivated in his work.

Only a handful of words escaped his scrutiny. Anticipating misinterpretations, he turned up and discussed every possible meaning and connotation. We eliminated terms with critical baggage and worked slowly toward the simplest of words: build, look, make, place, move, mistake, fail. Seator was always on the lookout for a phrase that reflected the multiple functions of his work: Planned Puddle, Places for Balanced Sculptures, a place for everything and everything in its place, and ultimately the title of our book, Making Things Moving Places. He was mindful of the ways description could turn to prescription, observation to interpretation. „The problem with describing the procedures used to make certain works is that it starts to sound like a set of instructions. It sounds like the work is just a matter of carrying out predefined procedures,“ he explained. Deciding where the balance tipped was a delicate matter. A description of a work could also lack grounding in the processes of making, with the result that „someone might think that the work could be made in any number of ways, that it‚“ just an illustration of an idea, and that’s really a problem.“

We would work and rework a paragraph until Seator felt it was under control and fully understood. The process would evolve over several days. Where we began in no way resembled where we arrived. Seator would be elated with the results. But at the start of the next day, I would find him agitated and pessimistic, regarding our previous week or two of work as if it were a complete stranger. „Why this word? What does this mean?“ he would ask. In a short time, those carefully honed phrases had just slipped away from his grasp. „This could mean anything…or nothing.“

What Cannot Be Done

Demoralizing as it was, Seator and I went on striving for control of something that would ultimately evade our grasp. This sort of failure differed from what I envisioned during our first conversation. I could not get my head around this situation and explain it. It was confounding and consuming.

As Seator continued to speak to me about his work and his life, he touched more frequently on the topic of failure. Once, as if by chance, he took a sharp turn in the middle of a conversation and recounted, very quietly, the many hours of his childhood spent exploring the floor of his home. Among the numerous attractions of electrical cords and outlets and small shelters offered by furniture, he recalled, in particular, a vast Kerman rug on the floor of his parents‘ bedroom. He would trace its elaborate border with his finger as he crawled around the rug’s perimeter, over and over again, one day after another, perhaps for a number of years. The rug had been purchased for Seator’s mother during her childhood, and it had extended just to the walls of her room, thus marking for the young girl the limits of her own domain. Three decades later, spanning the shape of floor between four different walls, the sprawling complexity of its surface seemed a world of its own to Seator. A small boy tracing its lines would have found figures and flourishes in the measures of small hands and feet. A mind and body could easily be lost in such a rug, though it was something other than a sense of playful abandon that brought Seator back to this surface one day after another. His interests merged with the continuous lines of the border, and as he followed with his finger along the unbroken enclosure, he sought to attain it rather than be lost to it. It was a ritual of control and self-soothing, Seator reflected, a struggle to know and experience, in an immediate way, all at once, the entirety of the border that enclosed the rug’s interior. Despite his persistent efforts, he said, he could never verify through direct experience what he knew to be a single stable entity.

He never mentioned this again.

It was only a short leap from the border of the rug to the perimeter of a room, which he began to investigate in 1990, and, then, to the entire surface of an architectural enclosure, which he took on for the first time in 1994 with Preventative Measures and then Entrance at the Neuberger Museum in Purchase, New York. „You know that the place you’re in is one thing, but it can’t be experienced as one thing. You can’t take in a room in one view, one snapshot, one position of the eye. It takes hundreds of positions of the lens to get it.“ Nevertheless, this was what Seator was trying to do: experience a portion of the world precisely as he knew it to exist. „It’s about reconciling what’s known with what’s experienced,“ he offered.

The tasks he set for himself – observing his immediate surroundings and representing or rebuilding them in the most literal manner – were at once dumb and profound. „I think there’s a connection, you can imagine, to a child setting out to rebuild the world one brick or stone at a time,“ he commented. The child would proceed, at first unperturbed by warnings of impossibility, trying one thing after another in order to master the world and remake it. At some point, the child would face defeat. „There’s always a point of letting go…accepting that it can’t be done,“ he told me about his own projects. Through failure, he suggested, it was possible to unearth a great deal more about the self and one’s surroundings than one might expect at the outset. It was one thing to speak of impossibility, another to carry it out, to be invested in failure.

„There was an aspect of retraining, or relearning, in these works,“ Seator explained. „The work was a way of looking at…gaining access to childhood training.“ By this he meant the ways a child learns to see, control the body, use and understand built space, and avoid transgressions of all sorts. He referred to his work as „an excavation“ of these aspects of the self and its relationship to the world, which he sought to „bring closer or move back or invert or push under the light for closer examination.“ The most fruitful method of performing this archeology of the self, he found, was to carry through a deliberate error. It could be a mistake of function or use, an error of maintenance, or a confusion of formal terms. It could be overwhelmingly ponderous or nearly invisible. Seator erred in all of these ways over the span of his career.

One project in particular continued to perplex him: Untitled (Interrupted Sweeping) 1991–95, which he carried out in his studio for more than four years. He called it „an exercise in bad housekeeping.“ He cut plasterboard from a wall of his studio and folded it into a scale model of his work space. This simple construction, consisting of walls and ceiling with one open side, was rotated ninety degrees counterclockwise and sealed to the studio floor with silicone. The model and the studio shared a common floor plane. Seator derived the dimensions of the model from the width and depth of his own body. „It was a sort of generic portraiture,“ Seator suggested. „I became interested in the standard body measurements used in design – the typical width of a doorway or the space needed to perform a common task like sitting or bending. I was interested in the ways these could be altered to a particular body.“ This plasterboard model of the studio, a small room scaled literally to the human body and made from the very walls represented, was one of many anthropometric mistakes. But it also provided a setting for errors of a different sort. Over a five-year period, Seator swept the debris from all of his studio activities onto the model, keeping the entrance and interior clear. „Instead of jettisoning all the waste, the dirt, the debris from my daily activities, I maintained it all inside the studio. It was a sort of retraining in the use of space, in the most basic way…It was really difficult at first. It was a violation of the idea that the dirt gets pushed to the outside. I mean, you talk about denial! You can go to therapy three times a week, or you can keep all the dirt inside.“ He was strangely animated when he spoke of this work. Was it amusement? Frustration? Anger? All of these? It was difficult to tell. „It was a very strange thing: object, context, and process all at once,“ he went on. „When you looked at it from the front, you could see inside, and the interior was absolutely pristine, and then the cut Sheetrock and the silicone were all that separated the clean interior from the debris. You could see this. I swept and observed the work almost every day, and I could never get that point of transition between the clean interior and the debris outside…that Sheetrock wall, I just could never get it.“ He appeared utterly bewildered when he spoke these last words. „I still can’t get it,“ he murmured.

Additional sweeping works were performed in several public locations, including PS1 in 1993, where all debris from Seator’s Untitled (Auditorium Installation) was maintained in neatly swept piles under a grid of lowered lights. „The floor had to be swept daily during the exhibition, and the janitor was responsible for performing this aspect of the work,“ Seator told me. „He wept. All of his activities were aimed at getting the dirt out, and now he was being denied the culmination of his labor. It was like leaving out a step, the most important step, really, the purpose. He broke down and wept.“

Other projects focused on problems of directly apprehending the surroundings – problems of vision, perception, concentration, and, ultimately, consciousness. In 1997, Seator brought together cement experts, surveyors, a utilities company, master masons, and a crew of about sixty builders, and set out to remake a section of the street, sidewalk, and façade of Capp Street Project within the San Francisco gallery. The work was titled Approach, in reference to an approach shot. „It’s the idea of a film loop. You cross the street with camera, you enter the building, and it repeats itself.“ Seator worked from a 150-point street survey, matching each of his materials to the original. Different gravel sizes were used to replicate various panels of the sidewalk. The curb was cast. Vaults and a utility pole, the latter „signed“ by the original tagger, were supplied by the local utilities company. Street lighting was replicated in the gallery. Even the slope of the street was rebuilt, pushing the highest point of the work forty inches above the gallery floor, with the fill underneath accurately constructed. The gallery’s corner glass entrance and side roll-up door provided views of what existed under the sidewalk and façade of the site. All that separated the street outside from the street inside was the windowed façade of the gallery, affording a view of one from the other.

When complete, the gallery held 250 tons of aggregate base and another 150 tons of concrete and asphalt. „I wanted to threaten the very structural integrity of the building,“ Seator explained. „In the end, the project had more oomph than the building itself. It would have been easier to pull off the outside of the building and leave the piece. At night there was an even greater sense of imposition, of weight on the building. You had a sense that this incredible volume of concrete had sought its level, had filled the gallery to its limit. But what was really remarkable,“ he continued, „was the way the work created a habit of vision. It made the street and its trajectory part of the work. The street was seen in a way it had never been seen before…it could never have been seen in this way. The work made the street visible, but it also made it unstable…unattainable. It was impossible to hold it in your mind, and people who spent time in it really tried and couldn’t take it all in.“

Approach was destroyed according to Seator’s instructions. „It was up for only two and a half months, and this was deliberate,“ he said. „I gave clear instructions that there would be no souvenirs taken, not even a piece of gravel.“

Doing Things Wrong

Not all of his works were temporary. Eight of Seator’s architectural reconstructions were conceived as permanent and transportable. These included Entrance (1995-95), Cabinet (1995), NYO+B (1996), BDO (1997), within the line of the studs (1997), Sculpture with French Desk (1998), Fifteen Sixty One (1999), and Places for Balanced Sculptures (2000). One of Seator’s highest priorities was to oversee the relocation of these works, but he had significant difficulties convincing others that the works could move to new locations. How could a work so thoroughly invested in its situation be pulled out of its original context and placed somewhere else? It was something here that it would not be there. Seator heard this often from presenters and audiences. His own declarations of his intentions had little effect.

Fifteen Sixty One was the centerpiece of this debate. Gagosian Gallery commissioned the work for its Beverly Hills location in 1999. Seator began the work process by scrutinizing the Richard Meier-designed facilities on Camden Drive, noting the dimensions of the roll-up door in the façade, „which was in the design of the gallery in order to bring in Richard Serra [sculptures] and Roy Lichtenstein paintings.“ Seator’s work would also enter through this opening, but not in the way intended. With tape measure and Polaroid camera in hand, he searched the streets of Los Angeles for just the right storefront to fit exactly into the 14.5-foot wide door. He intended to create a new address on Camden Drive and, at the same time, „to create a kind of blockage in the entry to the gallery“ by remaking this storefront and inserting it into the opening.

He narrowed the field from approximately one dozen to three possible sites: a check cashing business, a botanica, and a business offering public telephone services, all located in the Echo Park neighborhood of East Los Angeles. He observed the sites, sought out the owners, and explained what he intended to do. All agreed to cooperate. He settled finally on Popular Cash Express, located at 1561 Sunset Boulevard: „…the only two views out of [Gagosian] gallery are of banks and bank signage. One is Wells Fargo, which can be seen from the front. As you ascend the stairs…[you see] the sky first – this purely framed sky – and then you read, Bank of America. So I thought it made sense to add a third bank. Also I was attracted to the intensity, the zing, the incredible color of the Popular Cash Express logo – very intense blue.“

He went on to describe the process of remaking the storefront. „We matched the laminates that were used, which were often unmatched…We brought in hundreds of samples [to produce] dead matches.“ Inconsistencies in the moldings – for example, a bullnose corner next to a ninety-degree corner – were recorded and rendered. „The drawings would indicate all of these ostensible flaws and unmatched materials….We produced literally hundreds of detailed drawings.“ He continued, „I learned about security architecture…[The teller windows] are, in fact, bullet proof…made to specific ballistic standards.“ To reproduce the distinctive and abundant signage, Seator went straight to the bank’s own fabricator, „Victor Castañeda, an incredible sign maker…personally supervised this project.“

If every detail of the construction of this work was exact, then every aspect of its placement was exactly wrong. A deliberate mistake. The Beverly Hills Department of Buildings inspector let the gallery know, „This is precisely what we don’t want in Beverly Hills!“ According to the city’s building code, colored neon could not be visible from the street, but there were other, more socially motivated proscriptions as well, if one took the time to read between the lines. Seator discovered all of these in the course of situating the work. Several times he mentioned a visit from a woman who worked in Beverly Hills and lived in East Los Angeles. She came to Seator’s reconstruction just before the opening, elated to be able to cash her paychecks on her way home from work. „By the time she got home on the bus at the end of the workday,“ Seator explained, „the check-cashing businesses like Popular Cash Express had closed for the day. And, of course, there were none in Beverly Hills. This was going to make a big difference in her life. It really wasn’t easy to explain. She was disappointed.“ It was all in the building code, Seator pointed out, „It’s really disturbing. It’s a kind of apartheid code.“

Inside the gallery the work assumed a different identity, „a sculpture on plinths,“ which gave Seator recourse to a number of additional transgressions. A viewer could not enter Gagosian Gallery from the interior of the work, although the large ground floor exhibition space in which the work was situated could be seen through the teller windows. „You would enter this new address,“ by which he meant 1561 North Camden Drive, the address created by his work, and then, „come back out on the street, and, if you wanted, enter the gallery,“ one door down at 456 North Camden Drive. Under normal circumstances, a visitor would enter the front door, progress through the gallery’s entryway in the direction of the roll-up door, and turn left to enter the main exhibition space. „There’s an approach…and then the temple opens and the angels sing,“ Seator characterized what he believed Meier had intended. With Fifteen Sixty One firmly in place, however, this passage was completely obstructed. To accommodate the flow of visitors, Seator cut a new doorway into the exhibition space, admittedly attuned to the horror such an alteration would cause the architect.

Another facet of this error of placement was revealed from within the gallery: „It really [didn’t] use the space. It [was] very jammed in,“ he explained. The work was wedged tightly into the corner, leaving the remainder of the gallery noticeably vacant. „The space calls for monumental sculpture, soaring stuff, and that was precisely what I didn’t do.“ The exhibition also encompassed two photo-based works, which were presented in the smaller ground floor gallery and in an upstairs room, out of view from the primary space. „It was funny, but some people who came to see the work had a strong desire to fix the problem. One curator said the photographs upstairs should have been brought down to the main gallery to deal with the empty space. He was really disturbed by it.“

Seator intended Fifteen Sixty One to move somewhere else after this presentation. The storefront had already come across town. It was already out of place. Its situation was a mistake in every sense. Yet many viewers believed the work could not move beyond Gagosian Gallery. Given Seator’s finely executed placement of the work, the mistake was understandable. On many occasions, both private and public, Seator addressed the misconception: „There have been several situations in which it’s been explained to me at the end of a show, by a curator or gallerist, that…this work is so site-specific it should only be shown here – which was always informative,“ he explained in his final public interview with Thomas Crow. „Site-specificity seemed to be as far as they could go…I wanted to erase, for myself, the term site-specificity. Gently erase it…The works were written about as hyper-site-specific, and actually the works were fully transportable. Not so easy to do, maybe. It’s difficult for people to think about that, but…I wanted them to be transportable…in a way that would be analogous to a photograph.“

Seator was not just thinking about it. We was bearing the weight of his aspirations. With the exception of BDO, which was commissioned and acquired by the Whitney Museum of American Art, and Sculpture with French Desk, commissioned by Mary Boone Gallery and now part of the permanent collection of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, Seator was largely responsible for maintaining his permanent works after exhibition. The costs of storage were beyond his means. Sole responsibility for Fifteen Sixty One was shifted to Seator in 2001. The cost of maintaining this one work was five times the expense of storing all his other surviving works combined. He did everything he could. He diverted funds away from basic expenses such as utilities and taxes. He ran up his debts. In the end, his sole source of steady income, his home, was attached by the Internal Revenue Service. His telephone was cut off and all his utilities subject to termination. Through all of this, he was receiving letters threatening auction of Fifteen Sixty One because he was behind in his payments. „You think you’re some kind of artist, but all this just looks like a bunch of junk to me,“ the representative of the storage company offered his opinion. On June 5, 2002, Seator sent a message to me from New York indicating, parenthetically, „I don’t even have subway fare today, a bit bleak on my birthday.“ There was perhaps no better proof that he was serious about moving these works than the financial and logistical difficulties he endured to keep them safe…just barely.

He outlined various possibilities for Fifteen Sixty One: „At Gagosian Gallery, it was, ostensibly, architecture on the street – a new address – and a sculpture in the gallery. In that situation, it was stuck…between two realms, between these two identities, in the most literal way. It can be reinstalled in a large gallery at ninety degrees to the wall, and it will be a sculpture. It can be installed in West Hollywood where Banco Popular, the international bank with low production values, has some branches, and it will be clearly identified as architecture and quite invisible, not identified as art. Those situations are all of continuing interest – to think I’ve got it, but then I haven’t.“

This and That

One way and then another, Seator obstructed the mind’s progress toward closure and familiarity. To make an invisible world observable was a method, not his goal. Bringing the world closer, made it ever more difficult to attain. The world simply could not be mastered, and Seator carefully built and orchestrated situations in which this failure could be animated and experienced. It was true that a work was something here that it would not be there. But Seator had the last word on this subject: „Yes, it’s that, but it’s also this. It was a balance to keep the identities unfixed.“

Nina Holland

Los Angeles, 2005